Scientists have designed an immunotherapy that reduces plaque in the arteries of mice, presenting a possible new treatment strategy against heart disease. The novel therapy uses a lab-generated antibody to destroy a harmful type of modulated smooth muscle cell (SMC) located within blood vessel walls that plays a central role in driving inflammation and dangerous plaque formation in the arteries of the human heart. These cells directly contribute to coronary artery disease (CAD), in which atherosclerotic plaque builds up in the arteries that feed blood to the heart.

The team, headed by scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, working with scientists at Amgen, showed that in mouse models of atherosclerosis, specifically eliminating these cells using a targeted bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) reduced the amount of plaque, diminished plaque inflammation, and improved plaque stability, which is important for preventing heart attacks.

The study results suggest that the synthetic antibody-based therapy could complement traditional methods of managing coronary artery disease that focus on lowering cholesterol through diet or medications such as statins. Such immunotherapy could be particularly helpful for patients who already have plaque in their coronary arteries and remain at high risk of heart attack even if they’re able to achieve low cholesterol levels in the blood.

“We envision that this therapeutic approach would be ideal for patients with progressive coronary artery disease despite use of high-intensity lipid-lowering medications,” research lead Kory J. Lavine, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine in WashU Medicine’s Cardiovascular Division, told GEN. And while a timeline to IND will depend on lead optimization, Lavine noted, “current projections are within three years.”

Lavine is senior author of the team’s published paper in Science titled “Targeting Modulated Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerosis via FAP-1 Directed Immunotherapy,” in which the investigators concluded, “Our findings establish proof of concept for immune-mediated clearance of pathogenic SMCs and position BiTEs as a potential next-generation immunotherapy for CAD, with possible applications extending to other fibroinflammatory cardiovascular diseases.”

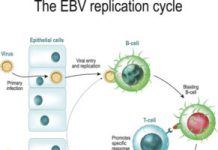

Atherosclerosis is an extremely common inflammatory process that chronically damages artery walls, often caused by a combination of factors such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and high blood sugar. Harmful immune cells accumulate and plaque builds up, forming a lesion that resembles a scar. As part of the process, structural cells called vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) in the arteries become dysfunctional, migrating to parts of the artery where they shouldn’t be. In these new locations, they become what are called modulated smooth muscle cells, which release signals that attract and activate inflammatory immune cells that drive ongoing plaque formation and instability.

“Atherosclerosis, a leading cause of cardiovascular disease-related mortality, is characterized by lipid-rich plaque accumulation, vascular remodeling and inflammation, and smooth muscle cell (SMC) dysfunction,” the authors wrote. “Medial SMCs maintain vascular integrity but undergo de-differentiation into modulated SMCs that migrate into the intima and contribute to plaque progression.”

To find a molecular signature of modulated smooth muscle cells, Lavine and colleagues performed a cutting-edge analysis of 27 human coronary arteries from patients undergoing heart transplantation. They used single-cell profiling that revealed the active genes and proteins in each of the 150,000-plus cells from these samples. They combined this information with spatial data specifying the locations of the various cells and cell types in the 3D structure of the artery, including within the arterial plaque. Using this single-cell and spatial “atlas” of human coronary artery disease, the investigators identified a molecule called fibroblast activation protein (FAP) as a marker on the surface of modulated smooth muscle cells.

“… we performed Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq) and single-cell spatial transcriptomics on healthy and diseased human coronary arteries,” they further explained. “We identified fibroblast activation protein (FAP) as a marker of modulated SMCs within the neo-intima, leveraged spatial transcriptomics to elucidate an immune-FAP cell niche, and applied genetic lineage tracing to define their origins.”

The researchers worked with Amgen to develop a half-life extended (HLE) anti-FAP BiTE that could grab on to modulated smooth muscle cells and enlist the destructive power of the immune system to eliminate them and their damaging downstream effects. “While BiTE technology has been extensively investigated in oncology to direct T cells against tumor-associated antigens, its application to cardiovascular disease is unexplored,” they pointed out. The BiTE molecule draws T cells to the target cell, whether it’s a cancer cell or, in this case, a modulated smooth muscle cell.

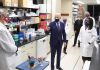

![An immunotherapy reduces plaque in the arteries of mice, offering a potential new strategy to treat cardiovascular disease, according to a study led by WashU Medicine researchers. An artery from an untreated mouse (top) shows more plaque (orange) than that of a mouse treated with the antibody-based immunotherapy (bottom). [Junedh Amrute]](https://www.genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/low-res-4-300x200.jpeg)

“This type of antibody therapy was originally designed to target cancers, such as lymphoma, and we imagine a similar precision medicine approach for cardiovascular disease,” Lavine noted. “Cholesterol-lowering medications are mainly preventive, which does not substantially reduce plaques that are already there. An immunotherapy that can reduce inflammation and dangerous plaque in patients with more advanced atherosclerosis is an exciting prospect.”

Experiments in mouse models confirmed that using the BiTE molecules to eliminate the harmful modulated smooth muscle cells significantly reduced atherosclerosis in these mice, compared with untreated mice. “BiTE treatment resulted in a marked reduction in plaque burden across mouse atherosclerosis models, suggesting that immunotherapeutic depletion of FAP+ cells may be a viable strategy for altering disease trajectory,” the investigators stated. “These findings suggest that depleting Fap+ cells with a targeted BiTE may offer a promising therapeutic strategy for mitigating atherosclerotic plaque burden while stabilizing lesions by directly removing modulated SMCs.”

Added Lavine, who is also the director of the WashU Medicine Center for Cardiovascular Research, “We found that these cells are located in areas of the plaque that are particularly vulnerable to rupture, which is the primary cause of heart attacks. What this BiTE molecule seems to be doing in removing these damaging cells is leading to an improved wound healing process, reducing inflammation and the amount of plaque, and increasing the stability of any plaque that remains.”

The researchers also employed an imaging tracer molecule that targets fibroblast activation protein, allowing them to use a PET/CT scan to locate modulated smooth muscle cells. In collaboration with their international team of scientists, they tested this tracer in patients with coronary artery disease and found that it lit up coronary plaques in the scans.

Lavine said they are planning more imaging studies and further optimizing the BiTE molecule to explore its potential as a safe and effective treatment for atherosclerosis. “The next stages of this project are to optimize the target killing efficiency of the BiTE and minimize cytokine generation to improve the safety profile,” Lavine explained to GEN. “Further testing will be pursued in humanized mice and human heart slices.”

The researchers aim to see if their imaging tracer could be used to distinguish stable versus unstable plaques, so they can try to prevent heart attacks in patients at the highest risk. “It is possible that differential FAPi uptake patterns across anatomical locations and patient groups may provide insights into stable vs. unstable plaques, and identify patients at risk for adverse cardiovascular events,” they wrote.

Lavine told GEN, “The imaging tracer is an active area of development for our team. We are particularly excited about the FAP radiotracer as it will enable the identification of patients most likely to benefit from the anti-FAP BiTE and allow investigators to noninvasively monitor treatment response in real time. This tool will propel clinical development of therapies targeting FAP+ modulated smooth muscle cells in CAD and other related diseases.”

In summary, the investigators stated, “Collectively, this work provides a detailed and comprehensive single-cell and spatially resolved map of human CAD, identifies FAP as a marker of modulated SMCs, and introduces BiTE-based immunotherapy as a potential strategy for targeting atherosclerotic plaques by depleting precise SMC-derived states found in human CAD lesions.”

Lavine further commented to GEN, “Our hope is that this single cell and spatially resolved map of human CAD opens up new avenues for investigators to pursue previously unrecognized target cell types and signaling pathways involved in the pathogenesis of this common and devastating disease. It will also allow selection of appropriate experimental models for target validation. This resource will be made available to the entire field.”

The post Immunotherapy Reduces Plaque in Mouse Arteries, Suggesting Coronary Disease Intervention appeared first on GEN – Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News.